STAT 479 Lecture 24

Decathlon Performance

Motivation & Setup

Decathlon Overview

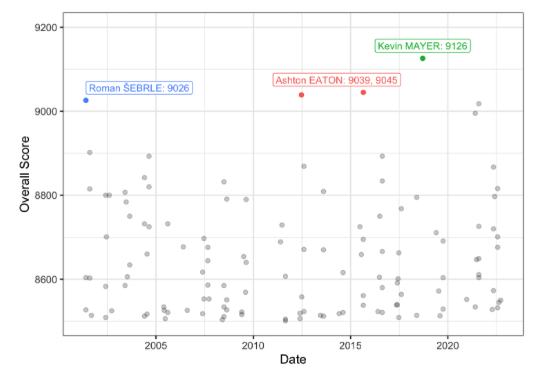

Best Decathlon Performances

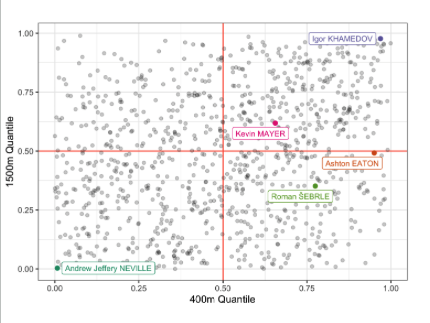

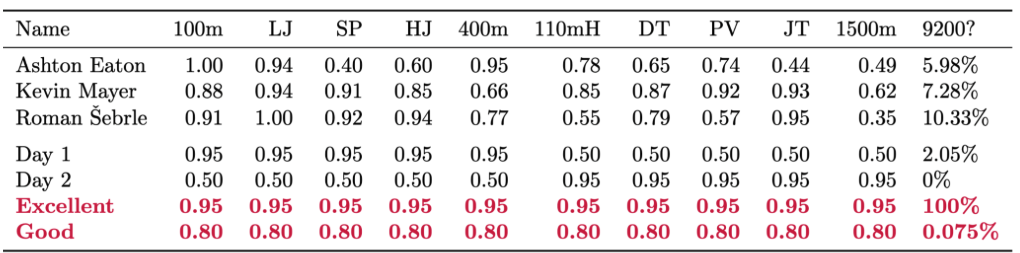

- Can someone break 9200? What would it take?

- Max out in one event? Be good but not elite at all?

Statistical Model

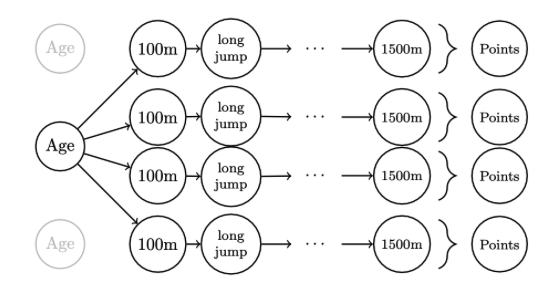

- \(j\)-th performance in event \(e\) by athlete \(i\): \[ \begin{align} y_{e,i,j} &= \alpha_{e,i} + \sum_{d = 1}^{D}{\gamma_{e,d}\phi_{d}(\text{age}_{i,j})} \\ ~& + \beta_{e,1}Y_{1,i,j} + \beta_{e,2}Y_{2,i,j} + \cdots + \beta_{e,e-1}Y_{e-1,i,j} + \epsilon_{e,i,j} \end{align} \]

- Athlete-event random effect: \(\alpha_{e,i} \sim N(\mu_{e}, \sigma_{e})\)

- \(\phi_{d}(x) = x^{d}\): allows for non-linear performance evolution

Model Fitting

Classical approach: maximum likelihood estimation

- Find \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}, \boldsymbol{\beta},\) and \(\boldsymbol{\gamma}\) that make observed data most likely

- Take STAT 310/312/410 for details

Use \(\boldsymbol{\hat \alpha}, \boldsymbol{\hat \beta},\) and \(\boldsymbol{\hat \gamma}\) to make predictions

Problem: how to propagate estimation uncertainty to predictions?

Digression: A Bayesian Approach

Types of Uncertainty

- Aleatoric: inherent uncertainty in a system

- Epistemic: due to ignorance/lack of knowledge

- Eg: consider a coin with unknown bias \(\mathbb{P}(\textrm{heads})\)

- Epistemic uncertainty about \(\mathbb{P}(\textrm{heads})\)

- If we repeatedly flip, we can learn \(\mathbb{P}(\textrm{heads})\)

- The more data we get, the less uncertainty!

- Aleatoric: uncertainty about result of next flip

- Even if we know \(\mathbb{P}(\textrm{heads})\), can’t perfectly predict next flip

- Can’t be reduced!

The Big Bayesian Picture

Quantify all uncertainties using probability distributions

Update, combine, and propagate uncertainty using probability calculus

General workflow: data \(Y\) and unknown parameter \(\theta\)

- Specify likelihood \(p(y \vert \theta)\) & prior \(p(\theta)\)

- Compute posterior distribution \(p(\theta \vert y)\)

Posterior quantifies uncertainty given the observed data

Example: Tea, Milk, Octopi, & FIFA

- Paul the Octopus: predicted football matches

- Picked from food boxes w/ nations’ flags

- Correctly predicted \(Y_{1} = 8\) out of 8 games!

- Milk or tea first?

- Muriel Bristol claimed to taste difference

- Correctly determined order in \(Y_{2} = 8\) out of 8 cup!

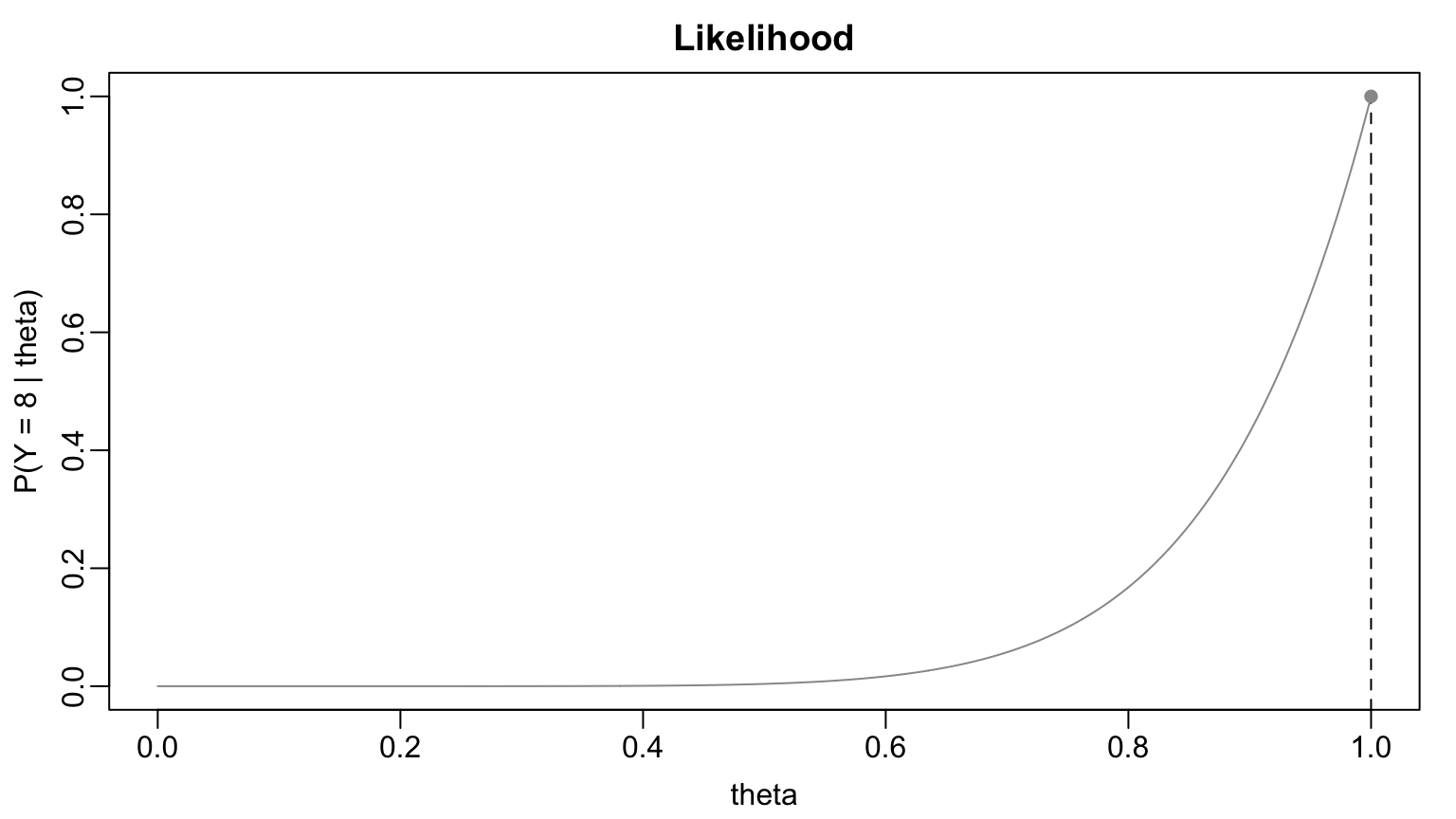

Example: Classical Statistics

- \(Y_{1} \sim \textrm{Binomial}(8, \theta_{1})\) & \(Y_{2} \sim \textrm{Binomial}(8, \theta_{2}).\)

- We observe \(Y_{1} = Y_{2} = 8\)

- Classical Statistics: \(\hat{\theta}_{1} = \hat{\theta}_{2} = 1\)

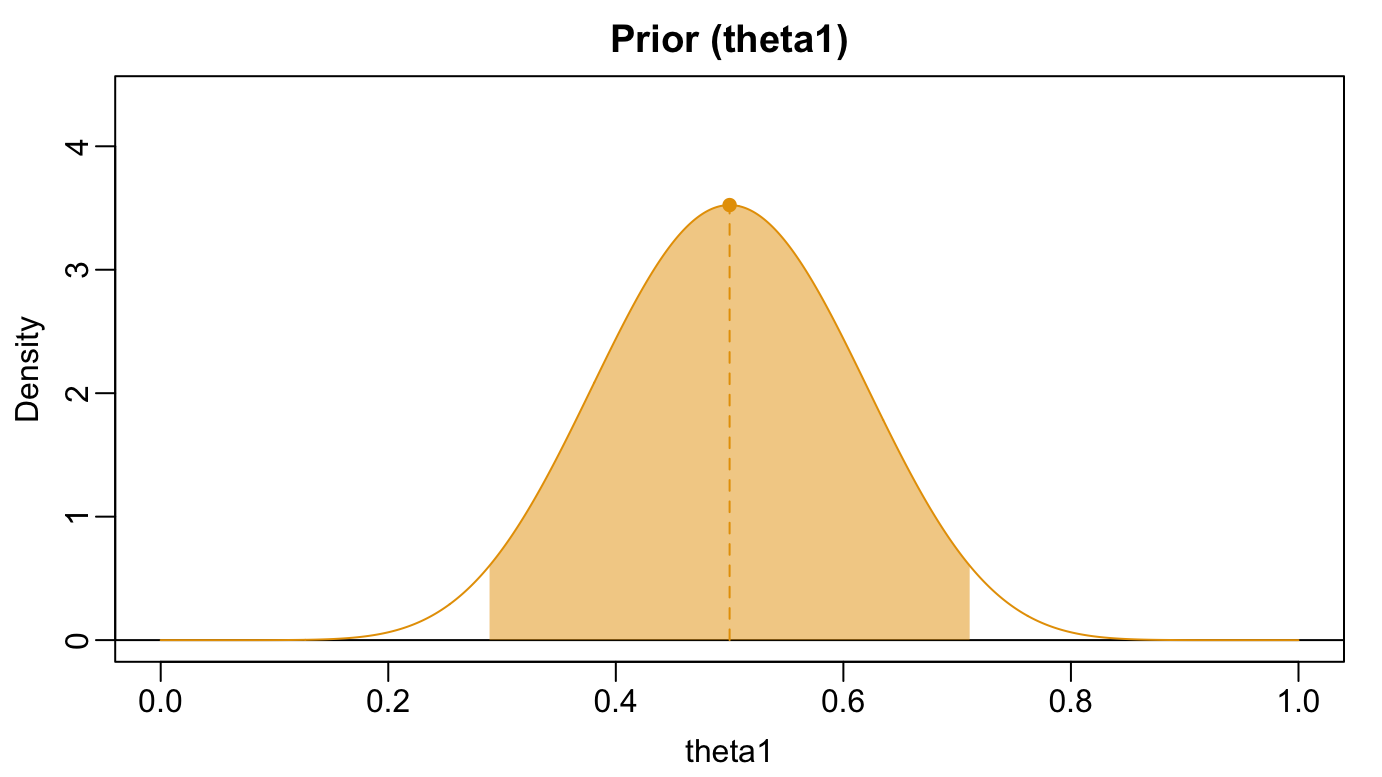

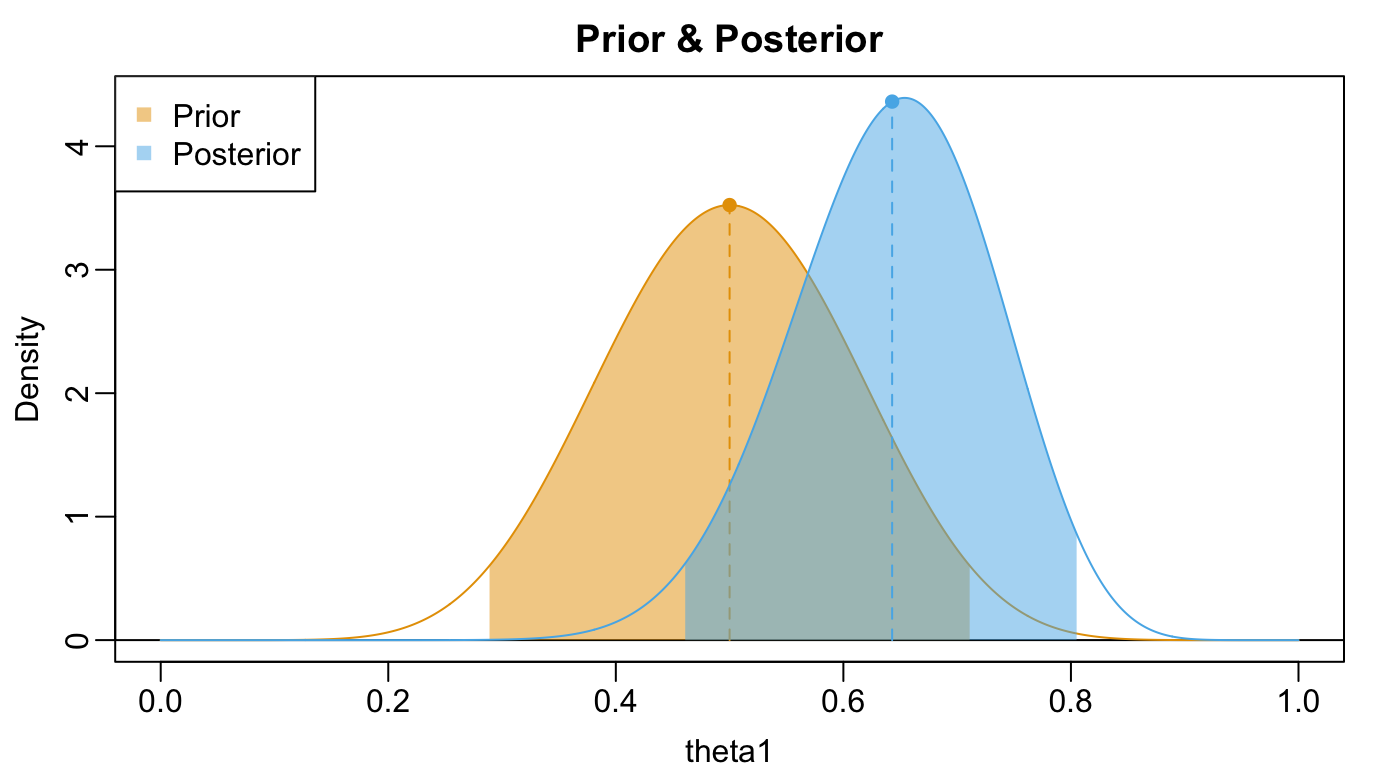

Example: Prior for \(\theta_{1}\)

- Relatively implausible that octopi know soccer

- More likely than not Paul is randomly guessing

- \(\theta_{1} \sim \textrm{Beta}(20,20)\):

Example: Posterior for \(\theta_{1}\)

- Posterior: \(\theta_{1} \vert Y_{1} = 8 \sim \textrm{Beta}(18, 10)\)

- Best guess: $_{1} = $ 0.64

- 95% interval: 0.46, 0.81

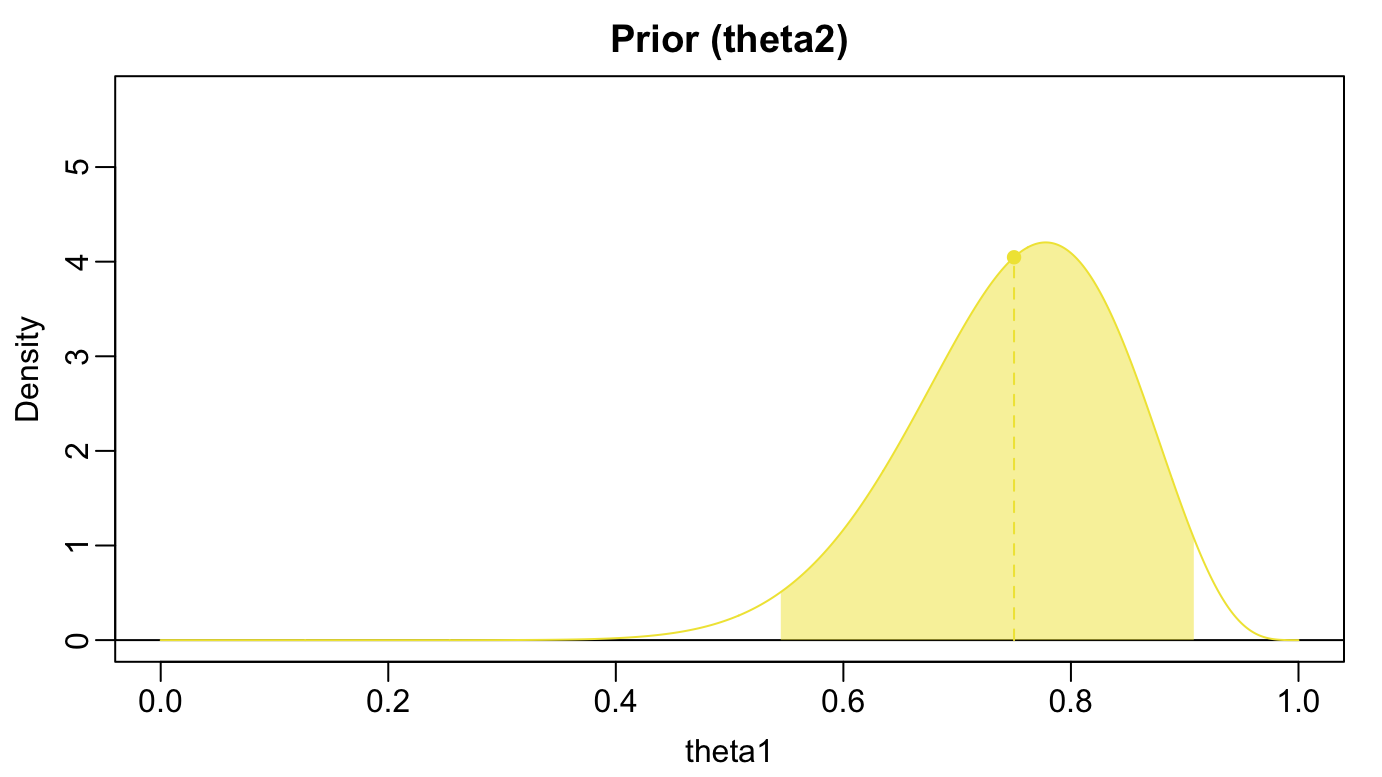

Example: Prior for \(\theta_{2}\)

- Plausible to refine palette over decades of daily tea consumption

- \(\theta_{2}\) is probably over 50%

- \(\theta_{2} \sim \textrm{Beta}(15,5)\)

Example: Posterior for \(\theta_{2}\)

- \(\theta_{2} \vert Y_{2} = 8 \sim \textrm{Beta}(23, 5)\)

- Best guess: 0.82

- 95% interval: 0.66, 0.94

Example: Posterior Predictive

- What if we asked Paul & Muriel for 4 more predictions?

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y_{1}^{\star} = k \vert Y_{1} = 8) = \int{ \mathbb{P}(Y_{1}^{\star} = k \vert \theta)p(\theta \vert Y_{1} = 8)d\theta}\)

- Simulation: for \(m = 1, \ldots, M\)

- Draw a posterior sample \(\theta_{1}^{(m)}\)

- Then simulate \(Y_{1}^{\star} \sim \textrm{Binomial}(4, \theta_{1}^{(m)})\)

n_sims <- 5e5

theta1_draws <- rbeta(n = 5e5, shape1 = a1_post, shape2 = b1_post)

ystar1 <- rbinom(n = 5e5, size = 4, prob = theta1_draws)

round(table(ystar1)/n_sims, digits = 2)ystar1

0 1 2 3 4

0.02 0.13 0.30 0.36 0.19 ystar2

0 1 2 3 4

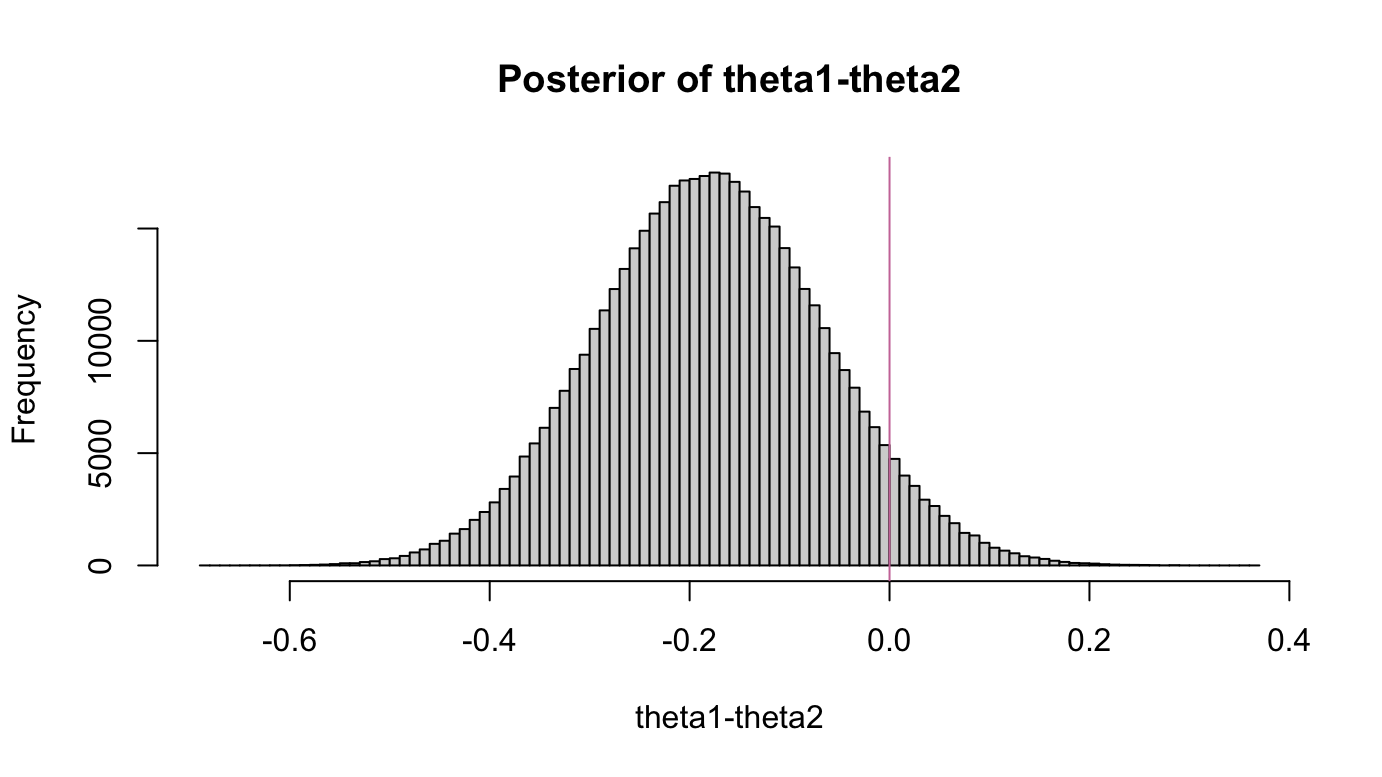

0.00 0.03 0.13 0.37 0.48 Example: Uncertainty about functionals

- Best estimate for \(\theta_{1} - \theta_{2}\): -0.18; 95% interval -0.4, 0.05

- \(\mathbb{P}(\theta_{1} > \theta_{2} \vert Y_{1} = Y_{2} = 8)\) = 0.06

Advantages of Bayesian Modeling

- Incorporate prior knowledge!

- Multiple parameter values can provide good fits to data

- No longer forced to commit to single estimate to drive downstream prediction

- Can make probabilistic statements: “93% prob. \(\theta\) lies in this interval”

- Sequential nature: use data to update prior beliefs

Bayesian Modeling in Practice

- Most posteriors are not standard distributions

- Must approximate posterior means, quantiles, etc.

- Markov chain Monte Carlo: construct a Markov chain whose invariant dist. is the posterior

Decathlon Modeling Results

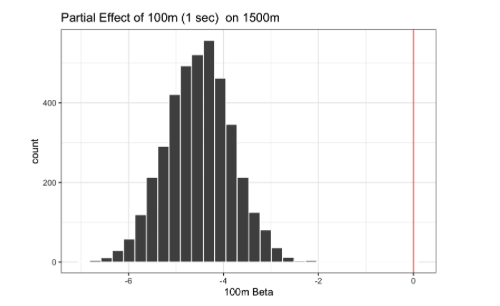

Inter-event Dependence

- .1 second decrease in 100m associated w/ ~24 second increase in 1500m time

- Posterior fully concentrated on negative values

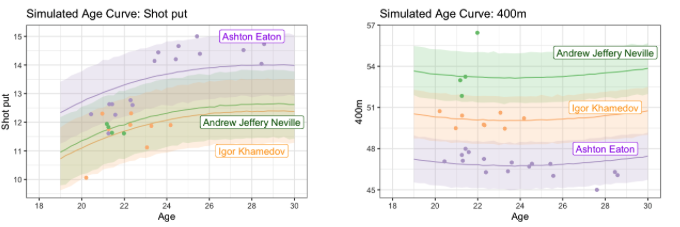

Posterior Predictive Simulation

For each posterior sample \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}^{(m)}, \boldsymbol{\beta}^{(m)}, \boldsymbol{\gamma}^{(m)}, \boldsymbol{\sigma}^{(m)}\): \[ \begin{align} y^{\star(m)}_{e,i,j} &= \alpha^{(m)}_{e,i} + \sum_{d = 1}^{D}{\gamma^{(m)}_{e,d}\phi_{d}(\text{age}_{i,j})} \\ ~& + \beta^{(m)}_{e,1}Y_{1,i,j} + \beta^{(m)}_{e,2}Y_{2,i,j} + \cdots + \beta^{(m)}_{e,e-1}Y_{e-1,i,j} + \sigma^{(m)}\epsilon^{\star (m)}_{e,i,j}, \end{align} \] where \(\epsilon^{\star(m)} \sim N(0,1)\)

\(y^{\star (1)}_{e,i,j}, \ldots, y^{\star (M)}_{e,i,j}\): sample from posterior of \(Y_{e,i,j}\) given all data.